-40%

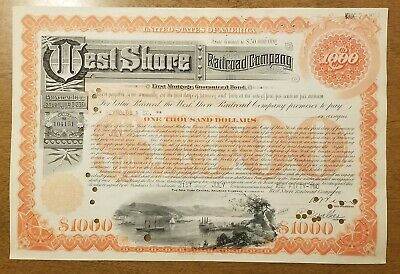

Oregon and Transcontinental Company Stock Certificate (1883)

$ 7.39

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

Product DetailsBeautifully engraved antique stock certificate from the Oregon and Transcontinental Company dating back to the 1880's. This document, which was printed by the American Bank Note Company, is signed by the company 2nd Vice President and Assistant Secretary, and measures approximately 11" (w) by 7" (h).

The detailed vignette features a pair of Native Americans looking down on a river valley. Pictured items include a train, a bridge, a boat and a covered wagon.

Images

You will receive the exact certificate pictured.

Historical Context

With the formation of the Oregon and Transcontinental Company begins the regime of Henry Villard, the dominating factor in Northern Pacific affairs for many years afterward. Some years before, Villard, who had long been interested in Western railroad enterprises and who had become prominent through his activities in connection with the Kansas and Pacific Railway, had succeeded in forming the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company as a combination of steamboat lines operating on the Willamette and Columbia rivers in Oregon, with an ocean line connecting Portland and San Francisco. A connecting railroad line, which had been built to Walla Walla in southeastern Washington, penetrated a portion of the territory through which the Northern Pacific was projected. In 1880 a contract was arranged between the two companies whereby the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company, in order to share in the traffic, undertook to construct a line eastward to meet the Northern Pacific line at the mouth of the Snake River. This arrangement would allow the Northern Pacific to run its trains into Portland and would obviate the necessity of constructing its own road into that city.

In spite of this arrangement, Villard feared that the Northern Pacific Company might decide, after all, to build its own line to Portland as soon as it was able to finance the project. It was for the purpose of preventing this move that he formed the Oregon and Transcontinental Company, a holding corporation which promptly acquired, in the open market and by private purchases, a dominating interest in the Northern Pacific Railroad. At the same time Villard placed the control of the Oregon Railroad and Navigation Company in the hands of the new Transcontinental.

Villard thus came to control the entire Northern Pacific system and, backed by the Deutsche Bank of Berlin and other German and Dutch interests, at once began an aggressive policy of expansion and development. The business of the system developed rapidly. The main line through to the Pacific coast was now in operation, and the entire system amounted to about 2300 miles of road. But Villard followed a financial policy which was not sound and paid dividends without justification. In a short time the company consequently found itself financially embarrassed.

As a result of financial losses in 1884, Villard was obliged to retire from active control of the properties. But in 1887 he once more got possession of the Northern Pacific with German capital and succeeded in arranging a lease of the Oregon Short Line, which had been developed by the Union Pacific interests, embracing a cross-country road from its main lines in Wyoming northward into Oregon and Washington. At the same time the interest of the Transcontinental Company in the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company was linked with the Oregon Short Line Company. These transactions, however, still left the Transcontinental Company in control of the situation, as it retained its majority ownership of Northern Pacific Railroad stock.

For the next few years the Northern Pacific did not follow a policy of rapid expansion. Other trunk lines, such as the Union Pacific, Rock Island, Santa Fe, Burlington, and North Western, were all growing and keeping pace with the rapid settlement of the West; but the Northern Pacific in these years simply rested content with its position as a single track transcontinental route having but few branches. Its only important extension was made by acquiring the Wisconsin Central Railroad, which gave the company a line between St. Paul and Chicago and a valuable and important entrance into the latter city. It was expected that, with this accession, the affairs of the company would be permanently established on a sound basis, but the overliberal policy of paying out practically all the surplus in dividends was continued in the face of large increases in fixed charges.

Early in 1892 it began to be rumored that the Northern Pacific was not in so easy a financial position as had been assumed. The stockholders took alarm; and the committee which was appointed to investigate the situation discovered a deplorable state of affairs. As a result of the severe criticism of Villard's policy, steps were at once taken to oust him from control, but without success until June, 1893. Two months later, receivers were appointed who discovered that the company was insolvent and had no funds to pay quickly maturing obligations. Receivers were appointed also for most of the branch lines, including the Wisconsin Central system. The Oregon Short Line, which was tied through guarantees with the Union Pacific although leased to the Northern Pacific, was involved in the general crash but was later separately reorganized.